The Congress stub terminal is seen looking east from State Street on May 23, 1939. The station was a very utilitarian affair, with the sizable station house on a track-level platform spanning the street, which was a fairly minor thoroughfare in its pre-parkway days. The Congress stub was less than 200 feet from the Congress/Wabash station, visible in the background under and behind the terminal structure. For a larger view,

click here. (Photo from the

Eric Bronsky Collection)

|

Congress Terminal

(500S/25E)

Congress Parkway and

Holden Court, Loop

Service

Notes:

|

South Side

Division

|

Quick Facts:

Address: |

14 E. Congress Street (station over street, 1950) |

508 S. Holden

Court (North Shore baggage office, 1953)

550 S. Holden

Court (North Shore baggage office, 1956) |

Established: June 6, 1892

Original Line: South Side Rapid Transit

Other Names: Old Congress, Congress & State

Skip-Stop Type: n/a

Rebuilt: n/a

Status: Demolished

History:

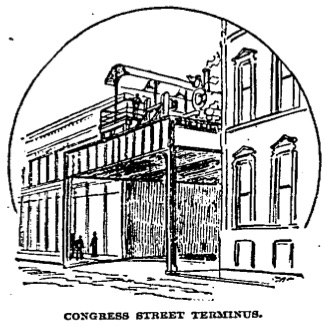

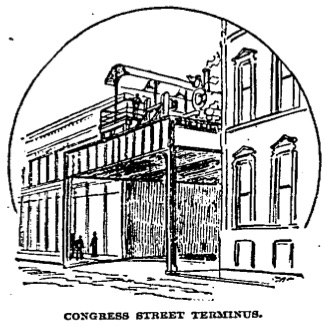

A drawing of the Congress Street terminal, as seen looking southeast from Congress Street, in 1892. Note the steam locomotive in the station and typical South Side Rapid Transit hump-backed platform canopy. (Image from the Chicago Daily Tribune) |

When the Chicago & South Side Rapid Transit Company (SSRT), the first "L" line,

opened in June 1892, the north terminal of the route was at Congress Street between State and Wabash, on the south edge of downtown. The terminal was compact by any standard -- the final block of the elevated structure, from Harrison Street to Congress Street over a narrow alley called Victoria Avenue (later renamed Holden Court), was designed to support two tracks, but instead was used to hold one terminal track on the west half of the structure and a single platform on the east half of the structure. The main line's double track may have extended a short distance beyond Harrison Street, but at some point in the vicinity of Harrison or immediately north the two tracks merged into the terminal's single track.

The track structure and platform ended at the south curbline of Congress Street (which was a normal-width street of only modest importance at the time). The station's single side platform consisted of a wood deck on a steel structure. The

platform's canopy was humped-shaped, typical of the original South Side Rapid

Transit designs. Unlike most other station's on the original SSRT line, which had their own station house under the elevated structure, when the line opened the station entrance at the Congress Street terminal was located in a building adjacent to the east side of the tracks, facing Congress and Wabash Avenue. As at other SSRT stations as originally configured, entering passengers passed a ticket office where they bought a ticket, then passed a staffed ticket box called a "chopper box" where their ticket was deposited before proceeding to the platform. Unlike other stations, this facility did not have restrooms.1

The tight, compressed accommodations of the Congress Street terminal facility were evident from the start. The Chicago Daily Tribune's coverage of the line's opening day dedicated some length of its coverage to the sub-optimal situation:

"Something should be done by the managers of the South Side Rapid Transit company to relieve the congestion at the Congress street station. As matters now stand not only is no provision made for the hauling of a crowd of passengers of any dimensions whatever, but the arrangement of the passengers leading to the platform of the station is such as to preclude the possibility of accommodating a rush. The first stairway leading from the street is broad enough, but after the second story of the building is reached quite a difficulty is encountered. Passengers fall into line and then force themselves into a narrow passage leading to the ticket-window, after which they take a tack to the right and ascend the stairs leading to the platform where the train is to be taken.

"In case of a crush at this narrow passageway--and there is always a crush where forty or fifty people come into the station at once in a hurry to take a train--the movement is so slow that a jam inevitably results, the consequence being that many persons must necessarily miss a train they could have otherwise taken. It is admitted by the elevated railroad people that the arrangement is a bad one, but promise that everything will be remedied before the World's Fair crowds come upon them. This, however, is hardly enough. A change just now would be welcome and result in increased passenger traffic. Many people yesterday, not caring to brave the crush at the ticket-seller's window, became disgusted and went away to take the cable cars, which, however crowded, admit the possibility of being boarded."2

In addition to the cramped passenger facilities, the single-track terminal also created some operational challenges, especially since the line was hauled by small steam locomotives. The locomotive needed to be at the front end of any train, but because the terminals at both ends of the line lacked turning loops or passing tracks that meant when a train reversed directions and pulled out of the station the way it came what had been the rear of the train would become the front. To get the locomotive from one end of the train to the other, a spare or "relay" engine was used. In this operation, the incoming train would pull into the terminal and unload its passengers. A second "relay" locomotive, already on standby a short distance down the track beyond the switches controlling access to the terminal. The relay engine would be moved the short distance to the terminal and coupled to the back of the train (thus becoming the front the trip in the other direction), and the original locomotive at the other end would be uncoupled. Once the train departed, the first locomotive would move up beyond the switch into the terminal track and become the relay engine for the next arriving train. The procedure would then be repeated for each train. This relay operation was also used by the city's other "L" lines until each adopted multiple unit (MU) control (a concept pioneered by the South Side "L" in 1898), wherein the motors on any motor car could be controlled from any driving cab in the train.3 This operation had to be especially well-choreographed at the Congress Street terminal, since, unlike the terminal at the south end of the line which had two tracks, the Congress end had only one track. That meant that any train occupying the platform track was blocking any other train from entering the terminal; with trains scheduled to run as frequently as every 2-1/2 minutes during rush periods, this meant trains needed to "change ends" and the relay engine operation completed quickly to avoid making trains wait outside the terminal for the track to become available, causing delays.

During the Columbian Exposition (1893 World's Fair), heavy crowds used the South Side "L" to get to the fairgrounds in Jackson Park. Dedication ceremonies for the Fair were held on Friday, October 21, 1892 (though the fairgrounds would not actually opened to the public until May 1, 1893). On Dedication Day, October 21, the Alley "L" transported 114,400 passengers; in the three days of the celebration, the railroad handled over 257,000 people. The Chicago Daily Tribune reported that Congress street station had a capacity of 9,000 persons an hour. The Tribune reported that the company had plans for the enlargement of Congress street station, but that the company officers would not talk of this report.4

To help handle the Fair crowds, a second platform was added at Congress Street on the west side of the terminal track to separate boarding and alighting passengers. The SSRT also operated some express trains.

The use of an existing building on the corner of Congress and Wabash for the terminal's station facilities may have been short-lived. A July 22, 1892 article in the Chicago Daily Tribune mentioned the Alley "L" (a nickname of the South Side "L") had leased, or considered leasing, the property on the west side of the Congress terminal (the opposite side of the terminal track as the building that housed the station entrance when the line opened) for depot and office facilities. The Tribune reported that this lease plan "aroused interest and speculation as to the future movements of the company," but it unclear if this lease was ever executed and station facilities moved.

Eventually -- more likely instead of this lease, possibly in time for the World's Fair crowds, and perhaps being the enlargement plans that the company officers would not elaborate on to the Tribune -- the SSRT extended the elevated structure across Congress Street to support a new platform-level station house. The added structure was around double the width of the existing structure south of Congress, with the additional width extended to the west over the street. The track was not extended any farther north; instead, the added structure was entirely occupied by the station house and a walkway around it. The building, low structure of frame construction finished in an iron cladding, was situated in the center of the elevated platform, against the south edge, allowing one to walk on the east or west sides of the building and around the north side. Doors on the south side of the building led onto the existing station platform. Stairs to the street extended westward to both sides of Congress, with a third descending eastward to the south side.

By October 1893, press accounts of the high ridership caused by the Fair refer to "stairs leading to the Congress and Harrison street platforms", suggesting that passengers entered the station directly from stairways from the street by that time and thus that the station house over Congress Street had been built and was in use by that time (as well as that there had perhaps been stairs added at Harrison Street to access the terminal platforms from the south to add capacity; if so, these were later removed).5

Later, possibly soon after the Fair ended and traffic returned to a more normal level -- the station returned to only one platform, the other having been removed.

Closure, Then Reactivation

On October 18, 1897, the

Union Loop opened and all South Side trains were

rerouted there. The track connection between the South Side Elevated's line and the Loop was made at Harrison Street, south of the Congress terminal. The South Side-Loop connector took the form of an extension of the two-track main line curving east at Harrison then back north over Wabash Avenue, creating one of the tightest S-curves on the "L", then two blocks north to Van Buren Street to meet the southeast corner of the Loop at a junction called Tower 12. Connection to the Congress terminal was maintained with a single track continuing north from the new curve at Harrison Street.

However, with all trains were rerouted to the new Loop -- and a new station at Congress/Wabash on the Loop connector a

half block east of the old terminal -- the small, one track station became superfluous and was closed. The dormant stub terminal was left in

place on the chance that it would be needed again.

That day was soon in coming. On March 10, 1902, the

terminal station was reactivated to several handle rush hour trains

that could not be accommodated in the Loop due to the downtown tracks having reached capacity. To distinguish

it from the Congress/Wabash station a

half block east, the Congress terminal was thereafter often referred to as "Old

Congress".

Between 1905 and 1908, the South Side Elevated opened several new branches and added service, increasing ridership and the number of trains servicing those passengers. The first section of the Englewood branch opened in 1905, and reached its terminus at Loomis/63rd in July 1907. A branch off the Englewood line to Normal Park also opened in 1907, as did the Kenwood branch which left the main line at Indiana and extended to 42nd Place at the lakefront. A third track added between 12th and

43rd streets to allow express trains to be added also opened in 1907. Finally, the branch to the Stock Yards, also leaving the main line at Indiana, opened in 1908. All of this added service needed someplace to go, and with the Loop close to capacity some trains were instead routed to the Old Congress stub terminal. Evidence suggests that trains to and from Old Congress alternated between the Jackson Park and Englewood branches (but did not serve the other branches), and that all trains from Old Congress were routed over the express track beginning in 1907.

To handle the added traffic, the old Congress station and tracks were remodeled in 1907 at a cost of $8,075. According to a 1908 report, "the platforms and stairways were entirely renewed, the station building was changed to conform to the new location of the platform, and the station and steel structure were thoroughly painted. In this connection it may be said that the advantages of train service from old Congress street station are beginning to be appreciated by the public. Traffic from this station has increased four-fold since the opening of express service, and it will be the continued effort of the management of this company to increase the business of old Congress street station by calling the attention of the patrons to the road--by means of circulars and otherwise--to the fact that by taking trains at this station, they will 'save time by avoiding delays to trains,'--'add to their personal comfort by getting a seat in the train which will be waiting for them,'--and obtain the advantage of express service south of Twelfth street."6

In 1911, the city's "L" companies formed a "voluntary association" under the name of the Chicago Elevated

Railways Collateral Trust (CER); in 1913, this coordination led to crosstown service being instituted between the North and South sides. While some South Side trains still only ran between downtown and the outlying terminal, particularly at rush hours, a large number were through-routed. As a result, the need for the excess capacity provided by the Congress stub terminal was reduced. Some scheduling information from 1913 suggests that Old Congress was

served only by Englewood trains. Morning rush hour service

was discontinued by December 31, 1914. However, trains continued to run south from Old Congress in the evenings.

North Shore Line Use and the Decline (and Eventual Discontinuation) of "L" Service

"L" service from the Congress Stub remained largely unchanged for the next several decades, consisting of extra service operating southbound in the afternoon and evenings.

However, not long after the level of "L" service out of the Old Congress began to decline, the stub terminal found a new source of traffic: the North Shore Line interurban. On August 6, 1919, the Chicago North Shore & Milwaukee Railroad extended

operations into downtown Chicago via the "L", with trains terminating at Roosevelt Road; from 1922 to 1938, trains

were extended farther south to Dorchester station on the Jackson Park

branch. Meanwhile, the interurban's main station and Chicago offices were at Adams/Wabash on the Loop.

Led by 'Baldie' 4000-series car 4112, passengers board the final departure of the day from Congress Terminal -- a 5:40pm express to Englewood -- on July 22, 1949. The station would close 8 days later. The station retained its original South Side Rapid Transit hump-shaped canopy until the day it closed. For a larger view,

click here. (Photo by Thomas H. Desnoyers, courtesy of the Krambles-Peterson Archive) |

The North Shore Line offered checked baggage service on certain trains, but it was not logistically feasible to have trains stand for extended periods to load baggage at Adams/Wabash on the Loop, or even at Roosevelt on the South Side elevated, due to the delays it would cause. The little-used Congress terminal, off on its own spur track and located only a few blocks from the interurban's main downtown station at Adams, provided a convenient location to handle and load baggage. Eventually, the North Shore Line leased space for a baggage room in a building at 17-19 E. Congress, immediately west of the stub terminal -- a loading dock in the alley under the "L" structure allowed for easy unloading of baggage checked in and brought from the Adams/Wabash station in the Loop, a freight elevator inside the building brought baggage up to platform level, and a doorway was added between the building and the train platform.

The North Shore Line scheduled its baggage-carrying passenger trains to avoid rush periods, when the Congress stub was used for "L" trains. The procedure was

for a combine car to be held open at Congress to receive baggage

and merchandise dispatch shipments until about 15 minutes

before a scheduled northbound departure from Roosevelt

Road, then run half a mile south to Roosevelt to couple onto the coaches.

When the State Street Subway opened on October 17, 1943, most through-routed trains were diverted off the Loop and into the new subway. The subway also had a station at Harrison, about a block away from the Congress terminal. The additional capacity afforded by the new subway opened up additional space for trains on the Loop "L" and further reduced the need for the overflow terminal at Congress. As a result, "L" service to the stub terminal was further reduced to a total of three trains per rush period.

This austere level of "L" service lasted just a few more years, and barely into the CTA era, until the new transit authority implemented its massive north-south service revision that streamlined service, instituted of A/B

skip stop service on the new North-South

Route, and closed 23 stations including the Congress Terminal. Effective August 1, 1949, the last "L" service was withdrawn from the Congress stub terminal.

In a view looking east circa 1953, the Congress Terminal station house over the street has been disassembled and removed, leaving only the steel platform over the street, which soon would disappear as well to accommodate the widening of Congress from a street into a parkway. The bare steel structure gives a good sense of the footprint of the former station house and the walkway around it. The Congress/Wabash station is visible in the background, also closed to passengers at the time of the photo. For a larger view,

click here. (Photo from the CTA Collection) |

The Congress stub facility continued in use as the

North Shore Line's baggage terminal, however. An unrelated city improvement project forced changes to the facility soon after "L" service ceased: the widening and extension of Congress Street into Congress Parkway as the eastern outlet of the new Congress Superhighway (later Eisenhower Expressway). The columns from the elevated structure over the street were an obstruction to the roadway widening; since the station house over the street was not used since the "L" withdrew service and no future use was planned, the whole structure over the street was removed. Ironically, this cut back the structure to a location similar to its original end when the line opened in 1892. By early 1953, the structure retrenchment was completed.

The building to the west of the terminal that housed the North Shore Line's baggage room was initially retained but cut back to clear the widened roadway, but by 1954 was bought by the city, completely demolished and replaced with a new city-owned multi-level parking structure, formally called Parking Facility No. 3. Designed by architect Everett Quinn, the parking deck was one of several the city built in the 1950s to encourage office construction and retain shoppers in the Loop in the postwar era when autos were quickly gaining dominance.7 The North Shore Line leased a 27' x 60' ground-level space inside the parking deck for use as a baggage room and office. A freight elevator was installed in the parking garage to connect the ground-level office and train platform, and the North Shore Line purchased and installed a Fairbanks, Morse 6,000-pound capacity floor scale for the facility; the pit for this scale was constructed as part of the building.8 The North Shore Line began using this new baggage facility effective May 4, 1956. This facility was actually closer to the Harrison Street end of the parking garage than Congress Parkway; this is demonstrated by the North Shore's last

public timetable of September 15, 1962 listing 550 S.

Holden as the

location of their Chicago baggage room.

By the early 1960s, a new platform with a wood deck and simple canopy with wood supports and roof was added along the west side of the terminal track; the original platform on the east side of the track was removed. It seems likely this occurred when the new garage and freight elevator came into use, since the elevator's location closer to Harrison Street would have made it hard to connect to the east platform across the track.

The North Shore Line continued to use the Congress stub until the interurban abandoned service on January 21, 1963. The Congress baggage room facility was officially closed effective this date. The stub track was not officially removed from service until November 20, 1964, though it had been inactive for that nearly-two-year period. It is likely that the stub track and structure north of the former Harrison Junction, where the spur connected to the South Side elevated's Loop connector curve, were demolished not long after.

The parking structure continued in use for another three decades, with the freight elevator in place within the structure but abandoned and essentially going nowhere (since the platform the upper-level doors opened onto had long since been removed), until

February 1998, when the city demolished both structures. The parking deck was initially replaced

with a surface parking lot, but eventually the University Center of Chicago was built on the block. University Center, a shared dormitory serving three different universities with campuses nearby -- DePaul University Lincoln Park Campus, Roosevelt University, and Columbia College -- plus 35,000 square feet of retail on the first two floors along State Street, was completed in August 2004. With the "L" structure removed (including the reconstruction of Harrison Curve in 2003, removing the last remnants of the Congress spur's one-time structural connection), Congress widened, and the reconstruction of the whole block to the west of the one-time elevated spur, there are no remnants left of Congress Terminal.

The former location of the Congress

Terminal station is seen looking east on September 30, 2002. This is the same location and

view as the photo above. The

South Side elevated (now the Green Line) still runs a half

block away over Wabash Avenue. Note that although Congress has

been widened (from a street into a parkway), most of the

same buildings are visible in both views, which was accomplished by taking over the ground floors of some buildings and placing the sidewalk within them as an arcade, leaving the whole right-of-way for the road. For a larger view,

click here.

(Photo by Graham Garfield)

|

|

harrison-holden01.jpg (153k)

Harrison Junction and its interlocking tower are seen looking north circa 1925. The two tracks curving to the right lead to the Loop, while the single track continuing north leads to the Old Congress station, whose single side platform and hump-roof canopy can be seen in the distance. A North Shore Line 250-class combine is loading baggage at the platform -- from 1919 to 1963, the interurban used the Congress stub terminal for loading and unloading baggage for its downtown Chicago passengers. (Photo courtesy of the Krambles-Peterson Archive) |

|

harrison-holden_1913.jpg (234k)

Layout of Harrison Junction in 1913, including the layout of the Old Congress stub terminal. (Reprinted from Instructions to Trainmen in Connection with Through Routing, issued by CER to employees in 1913, Graham Garfield Collection) |

Notes:

1. "Running on the 'L'." Chicago Daily Tribune. June 7, 1892, pg. 9.

2. Ibid.

3. Moffat, Bruce, The "L": The Development of Chicago's Rapid Transit System, 1888-1932 (CERA Bulletin 131), Chicago: Central Electric Railfans' Association, 1995, pg. 31.

4. "Hauled a Multitude: South Side Roads Carried 840,000 Passengers." Chicago Daily Tribune. October 30, 1892, pg. 10.

5. "Alley "L" Trains Are Swamped." Chicago Daily Tribune. October 10, 1893, pg. 4..

6. The Chicago Directory Company, Chicago Securities: 1908.

The Lakeside Press. 1908, pp. 178-179.

7. Chrucky, Serhii. "Municipal Parking Garages." Forgotten Chicago web site. December 13, 2008. Accessed March 26, 2022.

8.

Chicago North Shore and Milwaukee Railway. Annual Report for the Year 1955 - Way, Structures and Power Department. February 20, 1958, pp. X.

.